The public life of Muriel Lester (1883–1968) is a remarkable story of localised welfare work, interwoven with political activism on an international stage. It is a story that spans more than five decades and extends from east London to South and East Asia and the Americas. It overturns expectations of class and gender in the first half of the twentieth century – and it includes short but significant chapters on one of the world’s best-known civil rights leaders, Mohandas Gandhi.

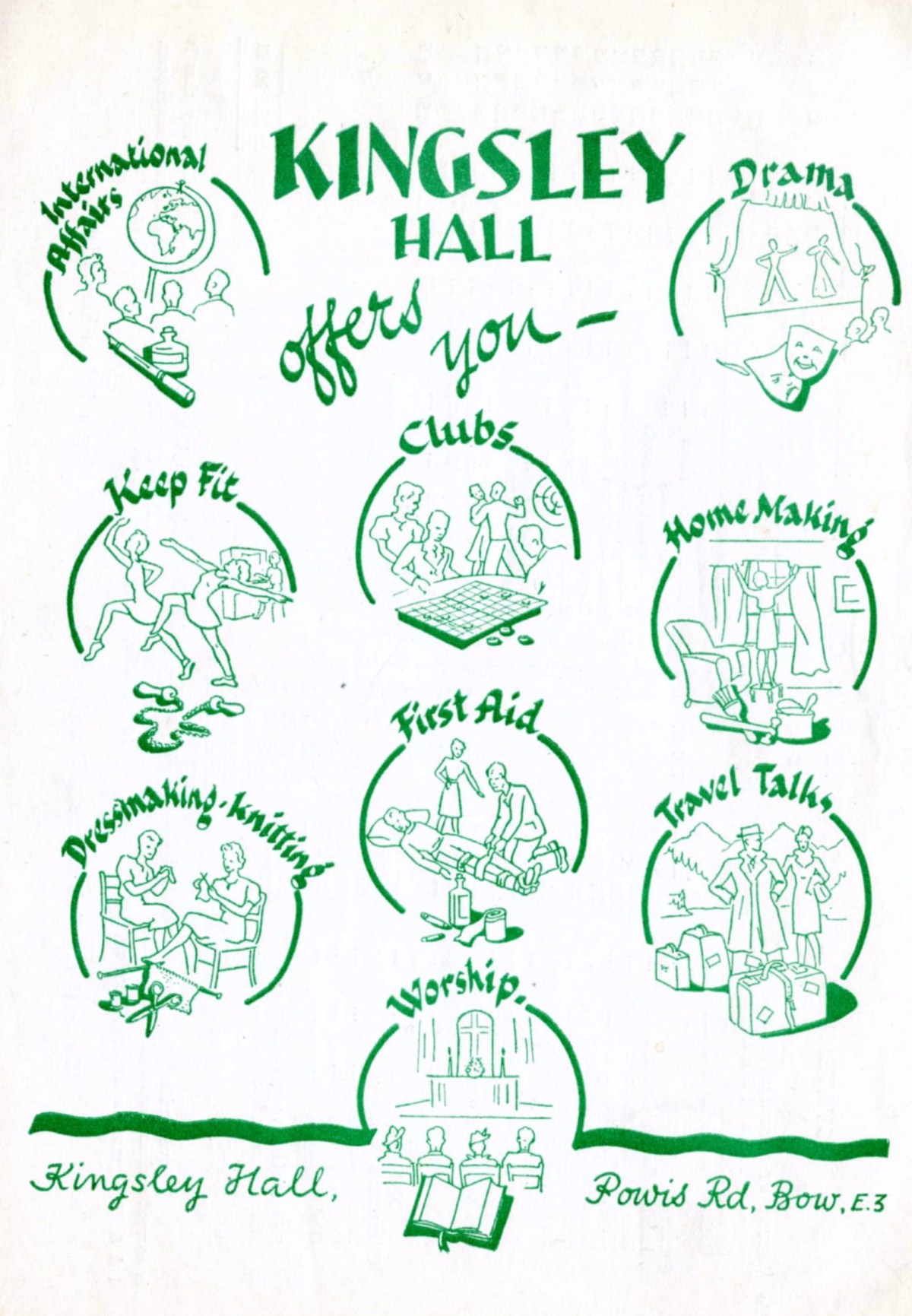

Muriel Lester’s informal social work started in the early twentieth century in Bow in east London. Shocked by the poverty she witnessed in her chance observations of the lives of the working classes and motivated by spiritually-informed notions of service, charity and social equality, Lester directly initiated programmes to provide free childcare for hard-pressed working families. She also personally stood on open-air platforms in Victoria Park and Hyde Park to speak out against militarism, and in favour of women’s suffrage; and she offered practical support to those affected by the General Strike of 1926. Perhaps her best-known achievement during this period was the establishment of the Kingsley Hall community centre in Bow where all were seen and treated as equal and all had equal access to a range of learning and leisure activities.

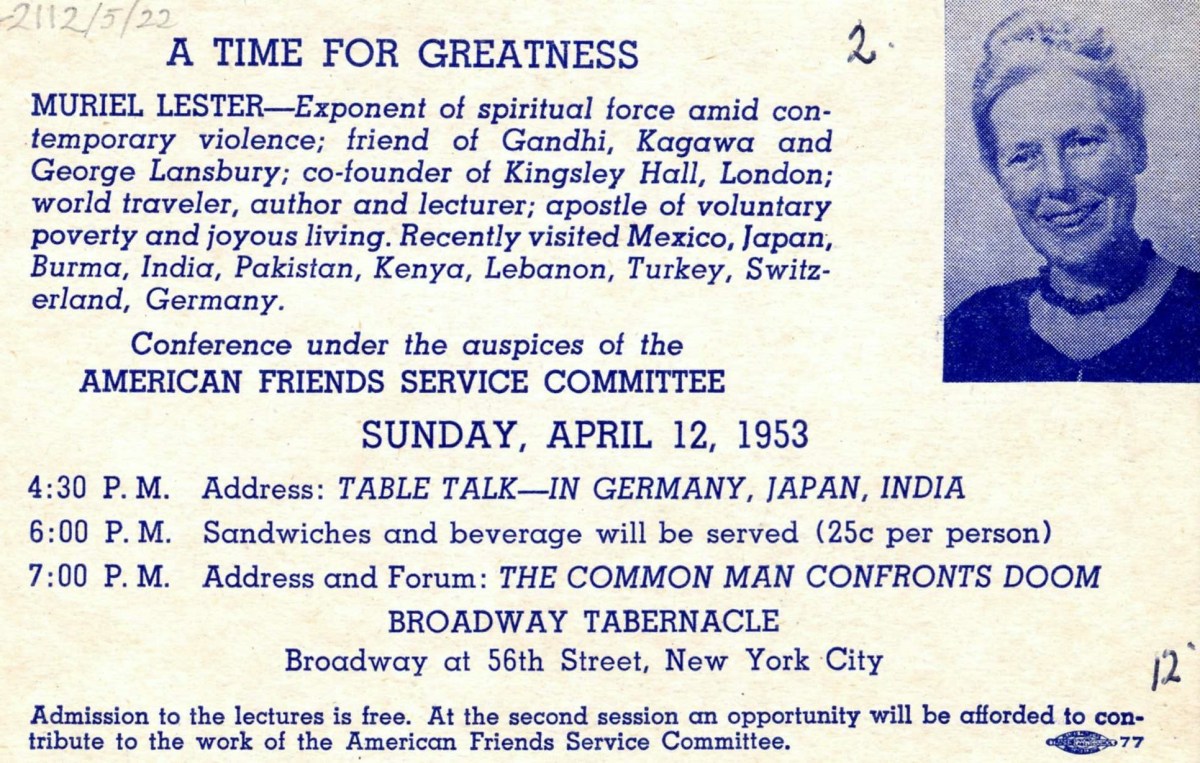

From the 1920s, Lester travelled across the world campaigning for peace and reconciliation between nations. It was during these travels that she met Mohandas Gandhi (1869–1948) in India in 1926. Sharing much in common – most notably their pacifist views and rejection of materialism – the two became regular correspondents and firm friends. When Gandhi visited London in 1931 he refused all offers of luxury accommodation in the West End, preferring instead to share the no-frills communal living enjoyed by Lester and other self-styled ‘apostles of voluntary poverty’ at Kingsley Hall in east London.

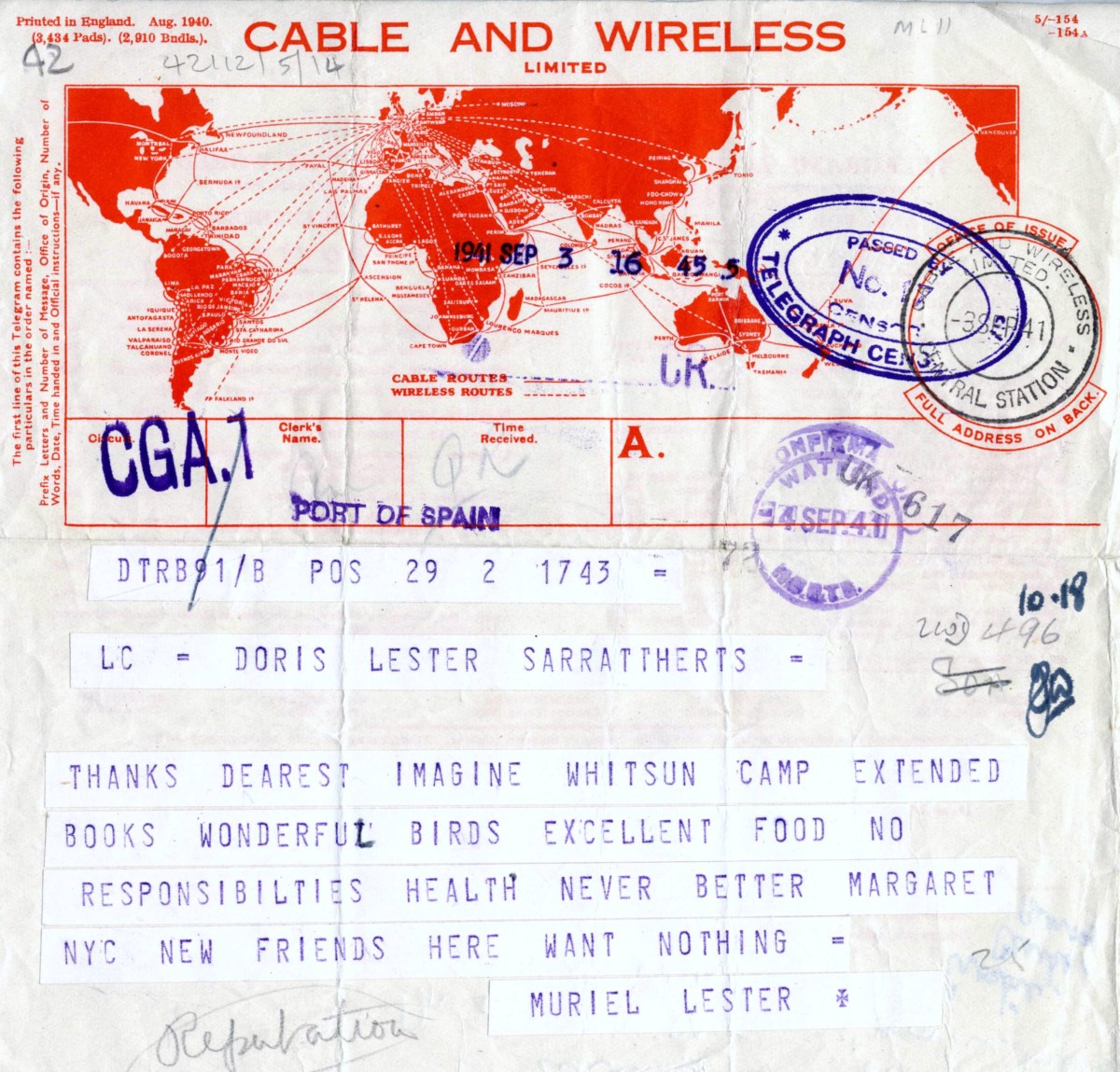

In 1941 Lester was partway through a speaking tour of America when she was arrested and imprisoned by British authorities at Trinidad. Speaking against militarism, at a time when Britain were engaged in World War Two, Lester’s actions were viewed by the British authorities as unpatriotic. At the time of her arrest, Lester was en route from South America to China, Japan and India via the United States. She was almost sixty years old. Fearing negative publicity, the authorities offered Lester hotel accommodation but – true to her egalitarian principles – she refused special treatment and insisted on serving her time in prison. As this telegram sent to her sister Doris during this period of incarceration shows, Lester accepted her situation with characteristic stoicism and good humour: ‘Imagine Whitsun camp extended. Books. Wonderful birds. Excellent food. No responsibilities. Health never better…New friends here. Want nothing.’

Alongside her international travels, Lester continued her work in east London. Her selfless and enduring contribution to local life across almost half a century was acknowledged when she was awarded the Freedom of the Borough of Poplar. The East London Advertiser covered the story on 6 March 1964:

‘In recognition of her eminent services to the people of the Borough of Poplar, particularly…her work in founding and maintaining the Kingsley Hall Social Settlement with the help of her sister, Miss Doris Lester; and in recognition also of her valuable contributions in wider spheres to the cause of world peace, the improvement of social conditions, the fight against poverty and disease, and the removal of race and class barriers, Miss Lester [has been] admitted an Honorary Freeman of the Borough of Poplar.’

In fact, Lester always objected to the term ‘settlement’, disliking the suggestion of patronage embedded within its meaning. Kingsley Hall had been run as a community-led initiative with local men, women and children involved in every aspect of decision-making from the first. But, the use of ‘settlement’ aside, this quotation neatly sums up the remarkable story of the life of Muriel Lester. This was a story both of its time and ahead of its time, most notably in its recognition of the need to remove ‘race and class barriers’ an ideal Lester not only promoted in theory but also practised in her daily life and activities.

To find out more about Muriel Lester

The images in this post have been reproduced with kind permission of Bishopsgate Institute. You can find out more about Muriel Lester by visiting the Bishopsgate Library where the Lester Archive is held. A pinterest board was created using items from this collection as part of The Only Way is Ethics project at Bishopsgate Institute in November 2013. This short article provides a useful summary of Lester’s life and achievements – with the emphasis on her spiritual convictions. An academic treatment by Seth Koven of aspects of the life of Muriel Lester is due to be published by Princeton University Press in autumn 2014. There are also rumours circulating of a feature film.